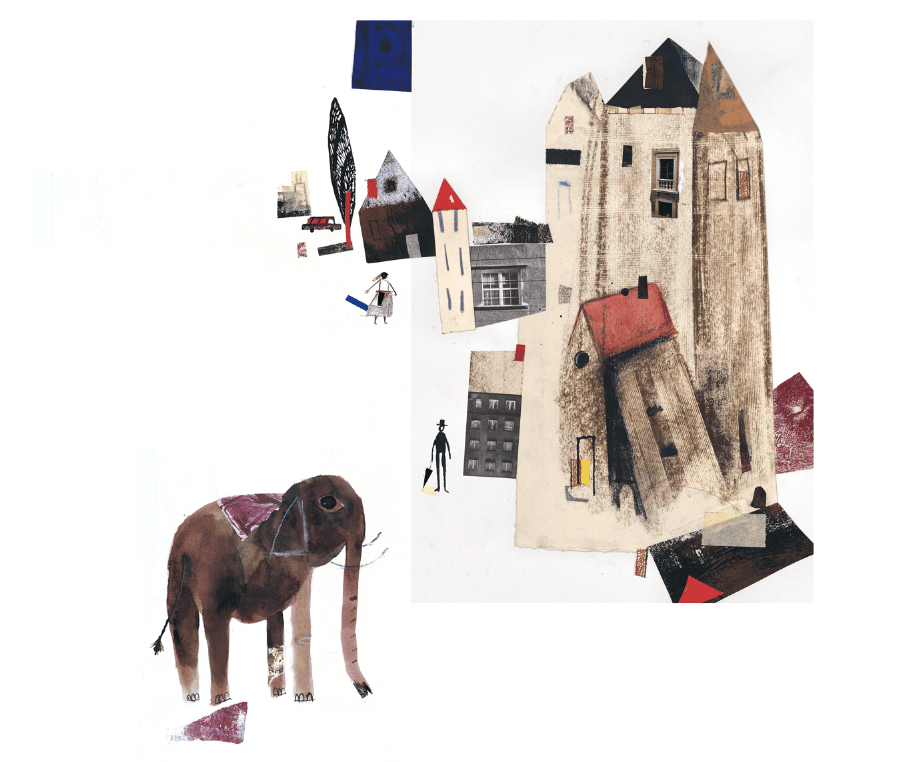

“Javier Zabala’s work is characterized by the combination of different elements and the expressionism he applies to children’s books. None of his works leave us indifferent; his avant-garde and pictorial language allows us to constantly discover elements that enrich the text. Each of the books the artist illustrates is different; he never repeats the same patterns, yet there is always something that connects them.”

– Rafa Vivas, Director of Iconi Master.

We spoke with Javier Zabala, one of the most popular illustrators in the world, about his perspective on contemporary illustration, the international workshops he organizes and the production processes of his projects before the workshop and exhibition he will organize in Istanbul. We wish you a good weekend and enjoyable reading!

Hello Javier, how did you decide to become an illustrator?

I have the idea that I always wanted to be an illustrator. At least since I was 10 years old when I discovered that drawing was something inevitable for me. I didn’t want to be a painter, or a sculptor, or a designer… I just wanted to be an illustrator and also a publishing illustrator… to illustrate books. And it was strange considering that when I was a child there were practically no references or visibility of the profession of illustrator…

To tell you how I started is a bit long, but to sum it up, I studied at the Art Schools of Oviedo and Madrid. Before finishing the fifth year I started my first professional jobs. Then I moved to Madrid, picked up the yellow pages phone book and visited publishers for about a month. And after a month, they commissioned my first two books on the same day: one in the morning and another one in the afternoon. I remember they gave me twenty days to finish them both and I lost 3-4 kilos in two weeks because of the stress, haha.

Actually this way of making yourself known or looking for a job would not work nowadays. Now all the projects are done through the internet and/or at most there is a phone call but no physical visits to the publishers. A vestige of how we did things in the 80‘s and 90’s is the book fairs. That’s where we still see each other’s faces. Fortunately.

Which projects have been the most challenging for you so far? Can you briefly tell us about your creative process?

I want to believe, and I always make this effort, that each new book is the most important one in my career, regardless of its visibility or the importance of the client. It is always a new link in my career and that seems important to me.

But of course, some projects have required more effort than others, but it is normally because I have a hard time finding a way to approach them and I have to work hard at this stage.

In general, these types of “more difficult” projects are the ones that eventually teach you the most and where you discover important things. They tend to be a before and after in the way you approach your work.

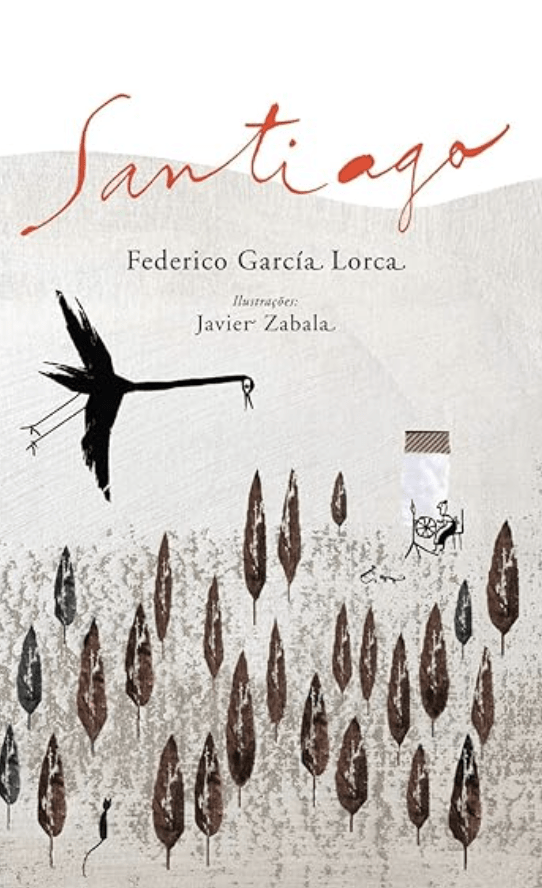

I remember, for example, “Santiago”, by Federico García Lorca. In this book I understood that I should always include something from my personal life and my culture in each project. And I had to start this book up to three times. On the third one, I realized that the book had to take place in the landscapes of my childhood, the north of Spain. From then on, everything was easy.

“Madrid for Children” published by the legendary Bohem Press in Switzerland was a huge challenge for me. I had to represent the city where I live and for that reason, I didn’t have enough perspective to see the city itself as a character.

And I remember that one summer afternoon the key to approaching the book from an emotional point of view came to me. I was watching a waiter serving a draft beer. The man’s face reflected the whole essence of what it means to be a Madrilenian. It’s difficult to explain but sometimes things like these are the ones that unlock a project.

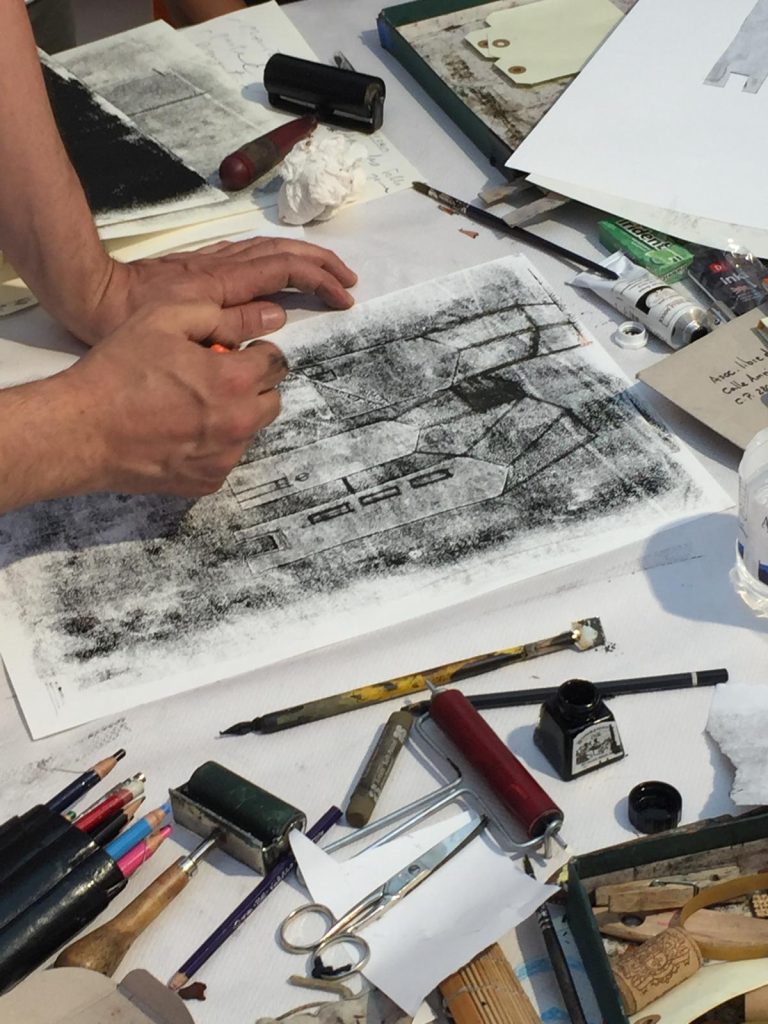

“The Caged Bird” with text by the painter Vincent van Gogh, was a book I worked on for four years and at the same time as another very ambitious book: “The Prose of the Trans-Siberian and Little Jeanne of France”, a magnificent poem by Blaise Cendrars.

In the first one, I never managed to make a connection between Vangogh’s pictorial world and mine. And in the second, the avant-garde movements of the 20th century guided me in the process. But by working on the two books at the same time, both were contaminated by each other. And they were graphically enriched, as almost always happens when something is mixed.

And of course. I could be writing for hours about each of my projects. They all have a story behind them.

You organise workshops in many countries. What can we find in your workshops?

After many courses and many years you come to the conclusion that in an illustration course the most important thing is to find your voice. In a course we can ask the necessary questions but not answer them. Answering these questions is what will make you recognise your graphic voice, that’s why only each person can answer these questions.

It is necessary to find your voice because without knowing it, it is impossible to start a project that is personal and not referenced to another artist/s.

The second issue that is important for me to work on in a course is ‘managing fear’ or tension, or creative stress or the pressure that we inevitably feel when making a project that will later be seen by many people. And that’s why we talk about ‘managing pressure’ because it’s the only thing we can do, learning to work with it, because it will always be there. I’m sure you’ve heard some very senior figures in the theatre admit that at 80 years old they still get nervous when they go on stage. Pressure, as well as never disappearing, is important for creating. But if you don’t manage it well, it can absolutely invalidate you. It’s a question of learning to redirect pressure into creative tension.

And it’s also a question of having the right attitude towards work. A veteran artist working on a project is sometimes happy with the result and sometimes not. But even when he’s happy he is not going to think he’s the best artist in the world and, of course, when things don’t work out he is not going to think he’s not good at all. If you have done a few projects you know that the creative process is like a saw blade with peaks and valleys. It is important to strive to stay focused on a medium emotional level and keep working. Only by working can you get out of the valleys of the saw, out of the dark moments. Obviously, if you don’t know how the creative process works, you may think you’re not good at it. But you have to keep working with confidence in the same process, which will take you upwards… working hard, of course.

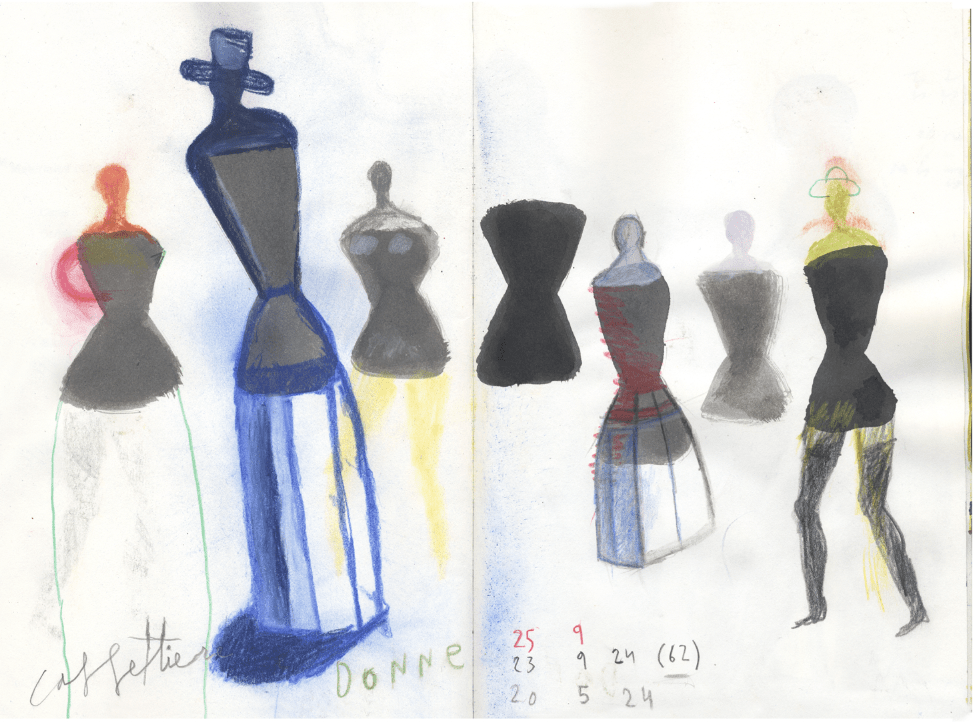

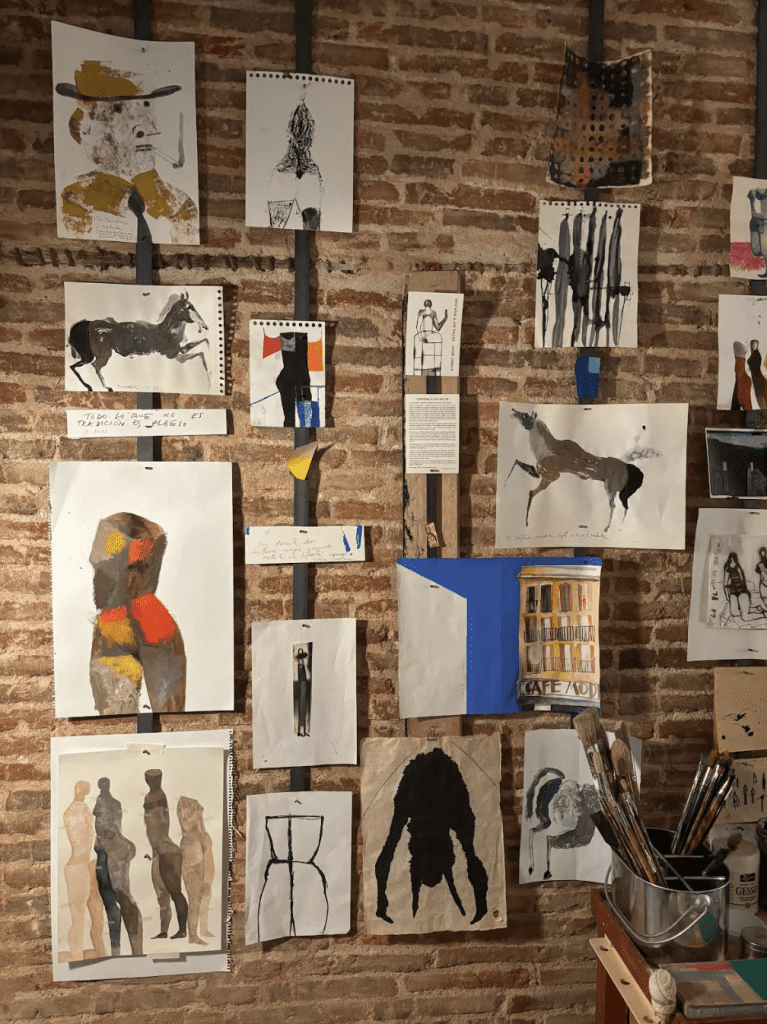

We also tend to deal with questions more related to techniques and procedures, which are also important as they help us to shape the alphabet of our graphic voice, for example, the plastic techniques themselves, the analysis of composition or rhythm in the book. We also study the influences of our masters and how to metabolise them and make them our own…

And then, even when we start to intuit what our voice is, we realise how important it is to protect it from any of the many external stimuli and at the same time to achieve spaces of creative freedom, like when you understand the true essence of a character, which allows you to work absolutely from your voice. And so many other things we don´t have space to include here…!

And each course is very much influenced by the participants themselves, their concerns and their desire to work.

We all work a lot in my courses, haha!

What inspires you the most?

Anything can inspire you if you’re attentive. Cinema, literature, poetry, a trip, a city, of course the people you meet, your colleagues, what you love, what you don’t… Everything you experience inspires you…

How do you see the future of the profession of illustrator?

I believe that an illustrator, like any other visual artist, shouldn’t have ‘surnames’ such as painter, sculptor, engraver, illustrator… The best artists have devoted themselves to whatever has motivated them at some point in their lives. We should engage in whatever we feel or want to do at any given moment. And that includes, as a possibility, all artistic disciplines: engraving, writing, painting, scenography, sculpture and of course also illustration… of books, press…

I see the future of artists as being very busy, as we have always been, and mixing many disciplines. Or not mixing them. But busy.

And then we have artificial intelligence…

It’s always a pleasure to chat with you. Thank you very much for your time!

Who is Javier Zabala?

He was born in Leòn (Spain) in 1962. He studied Illustration and Graphic Design at the Art School in Oviedo and Madrid. He has illustrated more than 80 books, and written some of them too. He has collaborated with some of the most prestigious publishers in the world and his books have been translated into 18 different languages. He has illustrated the works of Cervantes, Shakespeare, García Lorca, Rodari, Melville, Čechov, Van Gogh and many more.

He currently works both as an illustrator and as a professor, holding illustration courses and conventions at universities and art schools in Spain, Italy, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Iran, Cuba, Brazil, Venezuela, Israel, Singapore, Croatia, Portugal, Chile, Argentina, France, Malaysia, Russia, China etc.

His works have been displayed in many personal and collective exhibitions across the world. His many awards include: the National Prize for Illustration in 2005 and two honourable mentions for the Prize within the Bologna International Book Fair in 2008. He was one of the finalists at the Andersen Prize in 2012 and he was the candidate for Spain during the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award (ALMA). In 2015 he was awarded a Golden Apple at the Bratislava Biennale and in 2016 he won the Golden Medal of Times Illustration Book Award 2016 in China.

“During his brilliant career as an illustrator, Javier has undertaken some undoubtedly complex works, such as illustrations for “Don Quixote”, for “Santiago” by García Lorca (for which he gained an Honourable Mention during the Bologna Book Fair) and for an illustrated edition for adults of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”. He has also illustrated various stories by Melville and Rodari. In short, he made sure to gain a wide experience! He probably doesn’t hesitate when it is time to face new challenges, and this is an attitude that I really appreciate, because it shows a strong will to keep on evolving, researching and studying; a will that, in my modest opinion, a professional should never forsake. All of his books are different from one another, and yet they are united by a thread that resides in his sensitivity, in his vision of the world and in his ability to express them through images, adapting the language to every specific audience.” -Cristiana Clerici. Specialist in picture books (The tea box / Seven Impossible things before breakfast. Blogs).